| Home | Blog | Ask This | Showcase | Commentary | Comments | About Us | Contributors | Contact Us |

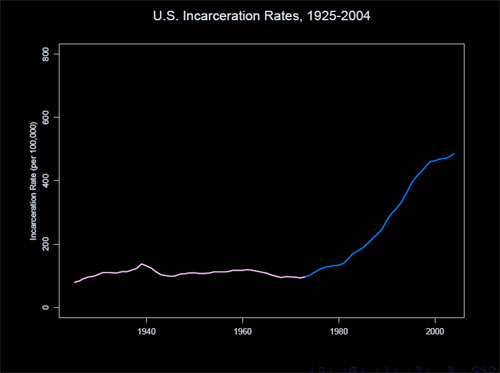

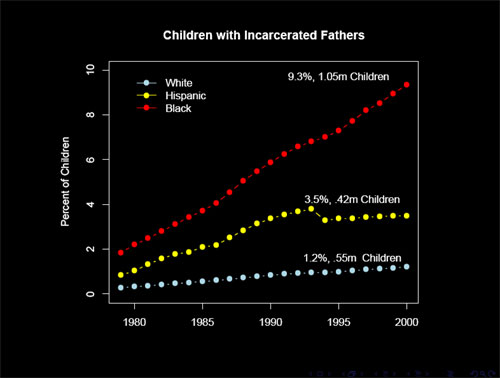

Does mass incarceration make us safer?ASK THIS | November 19, 2007Harvard sociologist Bruce Western writes that our society’s attempt to increase public safety through an ever-increasing reliance on imprisonment may instead be having the opposite effect, by undermining families and cleaving poor black communities from the mainstream of American life. By Bruce Western Q. Research shows that men who have served time in prison are less able to support their families, and more likely to be separated from their partners and children. Given that a steady job and stable family life are key steps to a life out of crime, how can our heavy reliance on prisons and jails sustain public safety? Q. Policymakers often blame family breakdown for the problems of drugs and crime in poor urban neighborhoods. Why, then, have they adopted punitive criminal justice policies that have pulled poor young men out of their families in such massive numbers? In its latest report, the Bureau of Justice Statistics announced that the rate of imprisonment in America in 2005 had climbed to 491 per 100,000. This marked the thirty-third consecutive year or rising imprisonment rates. There are now 2.2 million people in prison or jail, and another 5 million on parole or probation. Incarceration rates are highest among young black men with little schooling. The Justice Department reports that one-in-nine black men in their twenties are now in prison or jail. Among those who have never been to college, my own research finds that one-in-five are incarcerated, and one-in three will go to prison some time in their lives. For young black men today, a prison record is more common than a bachelor’s degree or military service. Annual reports on incarceration thus confirm not just inexorable prison growth, but also a transformation of American race relations in which the penal system now marks the road to adulthood for a generation of young black men. Are we at least safer with so many criminals locked up? Unfortunately, mass imprisonment offers few guarantees of public safety. My research finds that incarceration reduces the yearly earnings of ex-prisoners by 40 percent and increases the risks of divorce and separation. A steady job and a good marriage provide pathways out of crime, but incarceration undermines these steps to an honest living. How did we arrive at this self-defeating strategy for crime control? Conservatives say that incarceration rates are high among black, non-college, youth because they commit so much crime. Indeed, young black men are most likely to be involved in serious violence. Still, around half of all prisoners have been convicted of non-violent offenses. Most notably, blacks are about five times more likely to be arrested for drug crimes yet they are no more likely to use drugs. Liberals counter that poor job opportunities led young black men into drug dealing and other crime in the 1980s. However, blacks are seven times more likely to be incarcerated than whites but only twice as likely to be unemployed. Racial inequality in unemployment by itself is not sufficient to explain the racial disparity in imprisonment. Explanations that focus on crime and unemployment miss the critical role of public policy. Through the 1980s and 1990s, incarceration became the main punishment for felony offenders. In the 1980s, mandatory prison sentences were widely adopted for drug and other offenses. In the 1990s, parolees were returned to prison in record numbers for technical violations, and time served in prison was lengthened by truth in sentencing laws. The growing reliance on incarceration by lawmakers and criminal justice agencies reflected changes in philosophy and politics. Through the 1980s, policymakers abandoned the philosophy of rehabilitation. Keeping criminals off the streets and exacting retribution became the main goals of punishment. The abandonment of rehabilitation originated politically in the social turbulence of the 1960s. Crime rates increased in the decade after 1965, but civil rights activism, anti-war protest, and urban unrest also contributed to the anxieties of white middle class voters. In this context, the social problems of urban disorder, drug addiction, and idleness among young black men emerged as targets of penal policy. Politicians, particularly Republicans, and particularly in the south, cultivated a law and order message that converted anxiety into votes. Thus incarceration rates grew fastest under Republican governors and state legislatures, and in southern states like Louisiana, Texas, and Georgia. Mass imprisonment, then, is not the direct result of the social problems surrounding urban poverty, but a muscular – if ineffective – policy response to those problems. While the prison population increases with the inevitability of a rising tide, deliberate policy choice, produced by a combustible mix of racial and class politics, is the driving force. It is now time to reconsider our twenty-year experiment with imprisonment. By cleaving off poor black communities from the mainstream of American life, the prison boom has left us more divided as a nation. Incarceration rates are now so high that the stigma of criminality brands not only individuals, but a whole generation of young black men with little schooling. While our prisons and jails expanded to preserve public safety, they now risk undermining the civic consensus on which public safety is ultimately based. Following are two slides from a presentation Western gave at a recent conference at Harvard, The Moynihan Report Revisited. Here’s a podcast of Western’s presentation; here are the slides.

|

|

|||||||||||||