| Home | Blog | Ask This | Showcase | Commentary | Comments | About Us | Contributors | Contact Us |

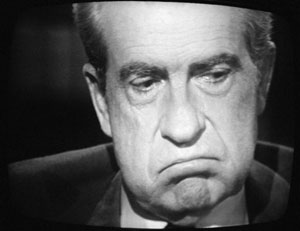

John Dean, on opening Nixon's grand jury testimonyCOMMENTARY | September 19, 2010In 1975, Richard Nixon testified before a California grand jury for 11 hours. Now a number of historians and archivists are petitioning to have what he said made public. This column first appeared in Findlaw. By John W. Dean Historian and Professor Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin Stanley Kutler, the American Historical Association, the American Society for Legal History, the Organization of American Historians, and the Society of American Archivists together petitioned the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia to request an order for the release of the transcript of former President Nixon's grand jury testimony of June 23 and 24, 1975, and associated materials of the Watergate Special Prosecution Force. These papers are currently under seal at the National Archives and Records Administration, pursuant to Rule 6(e) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. This petition is supported by sixteen declarations (running some 200 pages) from persons knowledgeable about the historical significance of Watergate and Nixon's testimony, including former assistant special Watergate prosecutor Richard J. Davis (who attended the Nixon grand-jury session), former Washington Post editor Barry Sussman (who put Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein on the Watergate story when it first broke, and became a special Watergate editor), former Assistant Chief Counsel to the Senate Watergate Committee David Dorsen (a former federal prosecutor and top staff man for the Senate inquiry), plus a host of prominent historians who have researched and written extensively about Watergate and Nixon. (Yours truly provided a declaration as well.) I have no idea what the Court will do, but I certainly hope that the petition results in the release of this material. Regardless, I find the situation fascinating -- both the law and the facts. The Law On Grand-Jury Secrecy--And Its Exceptions Most Americans do not like government secrecy. Yet grand-jury secrecy exists for a good reason. Professor Mark Feldstein, a former investigative reporter with a PhD in journalism who has written a terrific new book on Nixon and the news media, explains the circumstances nicely in his declaration: "Grand jury secrecy is designed to protect the rights of innocent people who may unfairly come under suspicion by prosecutors but ultimately are not charged. Secrecy can also help encourage witnesses to testify without fear of publicity and can prevent criminal targets from fleeing or destroying evidence, or intimidating or silencing witnesses." But there are exceptions. One such exemption applied when Chief Judge Henry Friendly of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit addressed grand-jury secrecy in a case where a candidate for mayor of New York City was claiming he had not taken the Fifth Amendment before a grand jury, when in fact he had. Judge Friendly wrote: " The tradition [of grand jury secrecy] rests on a number of interests -- the interest of the government against disclosure of its investigation of crime which may forewarn the intended objects of its inquiry or inhibit future witnesses from speaking freely; the interest of a witness against the disclosure of testimony of others which he has had no opportunity to cross-examine or rebut, or of his own testimony on matters which may be irrelevant or where he may have been subjected to prosecutorial brow-beating without the protection of counsel; the similar interests of other persons who may have been unfavorably mentioned by grand jury witnesses or in questions of the prosecutor; protection of witnesses against reprisal; and the interests and protection of the grand jurors themselves." But as Friendly's biographer David Dorsen notes in his declaration supporting the petition, Judge Friendly wrote the 1973 opinion for the court authorizing the release of the mayoral candidate's testimony because of the special situation. More recently, federal courts have found that Rule 6(e), the Federal Rule that codifies the grand-jury secrecy obligation, does not mean eternal secrecy for historically- significant information. A leading Second Circuit case, the 1997 ruling In re Petition of Craig , spells out the test for when such special historical circumstances exists. There, the Court noted a series of factors that are relevant in balancing the historical importance of the information sealed in the grand-jury record against the need to maintain secrecy. The Public Citizen brief that is seeking Nixon's 1975 testimony uses Craig's factors in petitioning the court for its release. Thus, the brief looks at: (i) the parties seeking disclosure; (ii) the party who opposes disclosure; (iii) the reason why the disclosure is requested; (iv) the specific information sought; (v) the age of the grand-jury records; (vi) the current status (living or dead) of those involved; (vii) the extent to which the grand-jury records have been previously made public, either permissibly or impermissibly; (viii) the current status (living or dead) of witnesses who might be affected by disclosure; and (ix) any additional need for maintaining secrecy. The Case For Releasing Nixon's Testimony Because the Nixon testimony is sealed, and the former prosecutors cannot talk about it (to the extent that they recall what was said), no one knows for sure what Nixon said during his two sessions and eleven hours before the grand jury. (Actually, two grand jurors and a team from the Watergate Special Prosecutor's Office travelled from Washington, DC to San Clemente, California to depose Nixon, and then the 297-page transcript of the deposition was presented to the other grand jurors. This arrangement was made because of the former president's ill health at the time.) Tracking Craig's criteria, the following facts are before the court as it decides whether to release the Nixon grand-jury material: (i) The parties -- those filing the petition -- are a "Who's Who" of Nixon historians, and their professional organizations; they are parties and organizations that have a professional interest in the historical Nixon. (ii) It is too early to know who, if anyone, will oppose the petition. I would be shocked if the Obama Justice Department opposed disclosing this testimony, but I would not be surprised if the Nixon Foundation -- which carries the torch for the Nixon apologists and Watergate Deniers (as David Greenberg appropriately labels them in his declaration) -- did file an opposition. Currently, the Nixon Foundation is fighting NARA, which now runs the Nixon Library, over the content of an honest exhibit about Watergate. As for criteria (iii) and (iv), the disclosure is sought based on what may be in the testimony. While the content of the testimony is not known precisely, news reports from that time suggested the general areas explored: what was said during the infamous 18.5 minute gap in the first recorded conversation Nixon had with his chief of staff following the arrests at the Watergate and whether Nixon was involved in erasing the material; Nixon's role, if any, in the alterations of the White House transcripts of the recorded conversations that were submitted to the House Judiciary Committee during its impeachment inquiry; the extent to which Nixon used the IRS to harass his political enemies; and the $100,000 campaign contribution from Howard Hughes to Nixon's friend Bebe Rebozo, which was never received by the campaign, but purportedly instead went to Nixon's brothers and his secretary Rose Mary Woods. Even if the press reports are wrong -- and I have no reason to think they are -- there is still a compelling case for releasing the grand-jury material. Nixon was the first president to testify before a grand jury, and the first president to resign from office, and his grand-jury testimony relates to the reasons why he left office, so it has true historical significance. To explain all this to the Court, the petition relies on the declarations of the historians who have spent decades writing about Nixon, and who all note that whatever Nixon may have said, given that it is all he has ever said under oath on these matters -- and given that, notwithstanding his pardon, if he lied, he could have been prosecuted -- it is historically important. As for the age of the records, item (v) under Craig's test, they are thirty-five years old. To address items (vi) and (viii), the current status of the persons affected by the testimony, Public Citizen lists thirty-three such persons as deceased. I added to my declaration, if my name came up, that I had no objection to the grand-jury records' release. Not knowing what Nixon said, I cannot think of anyone else living who might be mentioned by Nixon's testimony. The material that Public Citizen uncovered for item (vii), exploring how much or little of the Watergate grand jury testimony had surfaced, surprised me: Far more than I realized had come out, with a great deal having been leaked to syndicated columnist Jack Anderson, who was given several hundred pages of grand- jury transcript; plus the Watergate prosecutors used significant portions of grand-jury testimony in their indictment to show the perjury of H.R. Haldeman, John D. Ehrlichman, and John Mitchell. As for item (ix) of the Craig test, additional reasons that might call for secrecy, there are none. To the contrary, the declarations make very clear, and the Public Citizen brief supporting the petition effectively argues, that the traditional reasons for grand jury secrecy simply do not exist in this case. If this petition were in the Second Circuit, which has the greatest body of law on the subject, I would have little doubt that the Nixon testimony would be released. This petition is far stronger than the petitions in other cases where grand-jury testimony has been released. For example, much of the grand-jury testimony -- including that of Congressman Richard Nixon -- in the Alger Hiss perjury case has been released because of its historical significance. So too has much of the grand- jury testimony in the case that sent Ethel and Julius Rosenberg to their maker. There is only one problem with this petition: It is not in the Second Circuit. Waiver of Rule 6(e) -- the rule that mandates grand-jury secrecy -- is a matter for the Chief Judge of the U.S. District Court where the grand jury resides, and in this case, that is the District of Columbia. Thus, this case is before Chief Judge Royce Lamberth of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. While Judge Lamberth may find the law of the Second Circuit interesting, he is not bound to follow it. Nor would the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia be so bound, if Judge Lamberth says no and the petition is appealed. The U.S. Supreme Court has not waded into this area, so there is not unified federal law on this issue. This is another reason that this case is intriguing. Fortunately, Judge Lamberth is an independent-thinking jurist. It is difficult to believe that he is a judge who thinks our nation's history should be kept secret for nominal, if not technical, reasons. So we'll see. Allison Zieve, who runs the Public Citizen Litigation Group, has done a terrific job of assembling this petition, and presenting it to the Court. Here is a video of Allison summarizing a few key points. She was assisted by Julian Helisek, who did a lot of heavy lifting -- extremely well -- when gathering the historical material, and is now heading off to New York and private practice. It is reassuring to see a young attorney grasp the complexities of this history so quickly and so well. For any Watergate buff, the filings by Public Citizen to which I have linked in this column provide this history in a nutshell -- and 300 pages for Watergate, given the mass and difficulty of all the extant materials, is a nutshell. NOTE: In this column I wrote, somewhat awkwardly: “Not knowing what Nixon said, I cannot think of anyone else living who might be mentioned by Nixon’s testimony.” My thought would have been better and more fully expressed had I written that I cannot imagine Nixon’s testimony, whatever he said, adversely affecting anyone who might still be living. John Dean, a Findlaw columnist, was counsel to President Nixon.

|

|